The “Wheel of the Year” became widely recognized in the 1960s, primarily due to the growing popularity of Wicca. While Wicca is just one tradition within the broader umbrella of Paganism, it played a significant role in popularizing this seasonal framework in contemporary spiritual practice. However, it is essential to understand that Paganism encompasses a wide range of belief systems, and not all Pagans observe the Wheel of the Year. Reconstructionist traditions, such as Hellenism or Heathenry, often follow historical calendars and festivals that differ from the eight-fold cycle.

The Wheel of the Year and Its Eclectic Influence

Eclectic Pagans, along with much of the Neo-Pagan movement, have adopted the Wheel of the Year due to its accessibility and alignment with shared spiritual principles. The cycle emphasizes universal truths such as the cyclical nature of life, death, and rebirth, as well as themes of renewal, fertility, and harvest, which are central to many nature-based spiritual traditions. The Wheel provides a meaningful structure that connects practitioners to the natural rhythms of the Earth, which is vital to many Pagan paths.

An Overview of the Eight Sabbats

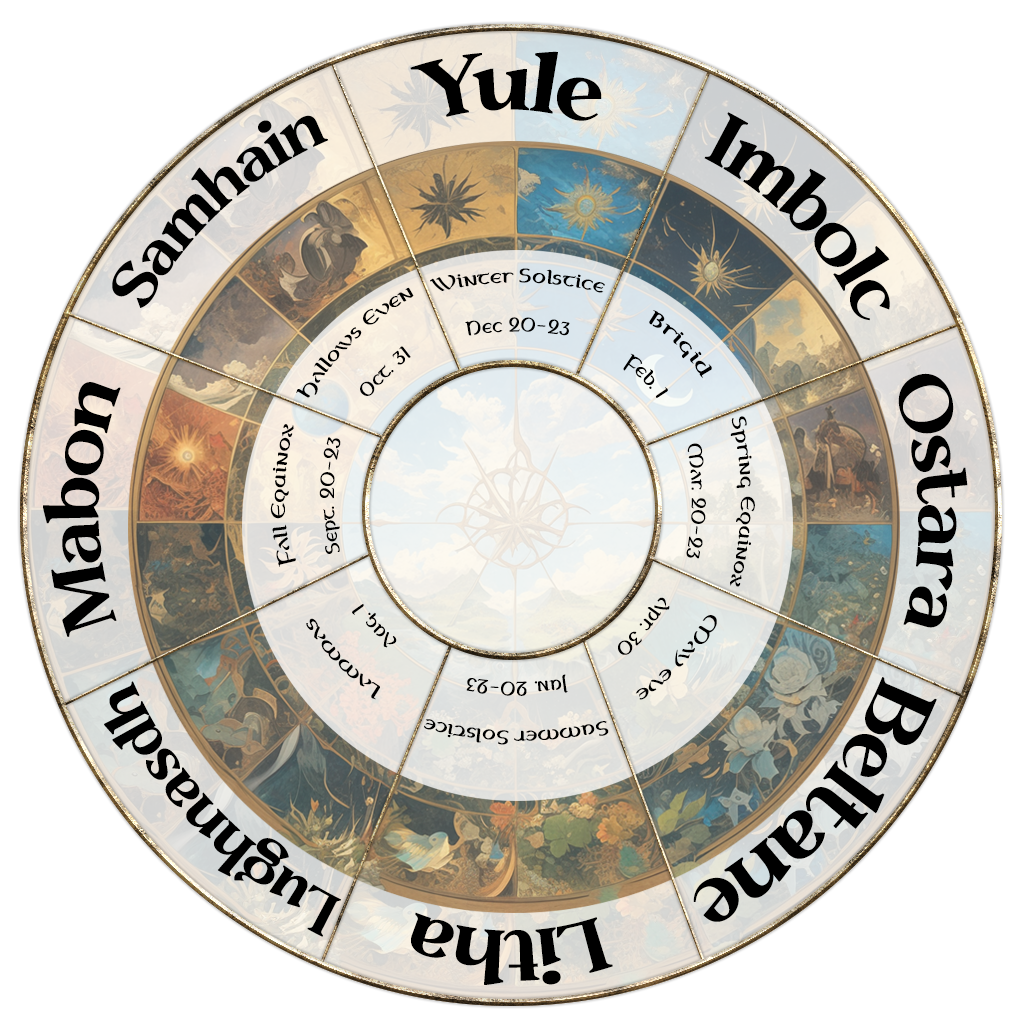

The Wheel of the Year is composed of eight festivals, or Sabbats, that align with key seasonal transitions. These festivals reflect both solar events, like the solstices and equinoxes, as well as agricultural and pastoral themes:

Yule (Winter Solstice): Celebrating the longest night and the rebirth of the sun, Yule symbolizes hope and the return of light. Traditionally, it involved feasting, fire, and gift-giving—customs that survive in modern Christmas traditions.

Imbolc: Occurring around February 1st or 2nd, Imbolc marks the midpoint between the Winter Solstice and Spring Equinox. It is associated with the first signs of spring and is often dedicated to the goddess Brigid, symbolizing purification and new beginnings.

Ostara (Spring Equinox): Around March 21st, Ostara celebrates the day of equal light and darkness. It marks the arrival of spring and is associated with balance, renewal, and growth, with symbols like eggs and rabbits echoing themes found in modern Easter traditions.

Beltane: Celebrated on May 1st, Beltane is a fire festival welcoming the height of spring. It is a celebration of fertility, abundance, and sensuality, with traditional customs like dancing around the maypole and lighting bonfires.

Midsummer (Litha or Summer Solstice): On June 21st, Midsummer marks the longest day of the year, celebrating light, warmth, and the peak of vitality. Rituals often focus on strength, energy, and success, with a special focus on honoring the sun.

Lammas (Lughnasadh): Celebrated on August 1st, Lammas is the first harvest festival, focused on giving thanks for the Earth’s abundance. Bread-making and sharing the first grains of the season are common ways to mark this festival.

Mabon (Autumn Equinox): Around September 21st, Mabon represents the balance between light and dark but shifts focus toward preparing for winter. It is the second harvest festival, emphasizing gratitude, introspection, and preparation for the colder months.

Samhain: On October 31st, Samhain marks the end of the harvest and the beginning of the darker half of the year. It is a time to honor ancestors and reflect on mortality. Many modern Halloween customs, such as carving pumpkins and wearing costumes, have their origins in Samhain.

The Wheel’s Ancient Roots and Modern Adaptations

Many of the Wheel’s festivals are rooted in ancient European traditions, and aspects of these celebrations have been incorporated into mainstream Western holidays. For example, Christmas has elements from Yule, such as festive trees and Yule logs, while Easter has drawn from Ostara’s symbols of fertility, like eggs and rabbits. These ancient festivals were often adapted by new religious frameworks, particularly during the Christianization of Europe, where Pagan holidays were repurposed with Christian narratives.

Reclaiming Spiritual Significance

Eclectic Pagans strive to reconnect with the original intentions behind these festivals. Rather than participating in the commercialized versions of holidays as seen in modern society, they focus on the spiritual depth and significance of the Sabbats. For example, Yule becomes a time to honor the darkness and celebrate the sun’s return, while Ostara emphasizes balance and fertility in alignment with nature’s rhythms.

Eclectic Pagans also emphasize philosophical and spiritual exploration over the material aspects of holidays. They view the Wheel of the Year as an opportunity to engage with nature and personal growth, exploring broader concepts like life, death, and rebirth. By focusing on the cycles of nature, they aim to foster a deeper connection with the Earth, valuing self-reflection and spiritual development over corporate-driven holiday customs.